The Intersection of Policy and Schistosomiasis on Neglected Tropical Disease Day

On this World Neglected Tropical Diseases Day, we invite you to learn more about science policy in the context of Neglected Tropical Diseases and why we must continue advocating for global support of and funding for evidence-based policies that limit their spread.

Written by SNAP Members Emily Selland and Becca Blyn

Footnotes are denoted with superscript. References are denoted with brackets.

Today is World Neglected Tropical Diseases Day! Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are caused by a diverse array of pathogens and disproportionately impact vulnerable populations in low- and middle-income countries [1]. They have devastating short- and long-term health impacts, cause chronic health conditions, and result in elevated morbidity (suffering) and mortality (death).¹ NTDs also result in heavy socioeconomic burdens on individuals and endemic countries [2]. For the past 6 years, on January 30th, the world has come together to recognize the impact NTDs have on society and re-commit to eradicating these diseases for good. World NTD Day commemorates the 2012 London Declaration, where global partners committed to greater financial investment and action against NTDs [3].

Even though NTDs affect more than 1 billion people each year, these diseases remain “neglected”: ignored, underfunded, and deprioritized [1,2]. The “neglected” status of NTDs is multifaceted and complex, arising from local and global factors [4], including but not limited to policy choices, colonialism, and resultant socioeconomic injustices.

Today, we will examine NTDs from a science policy perspective: what policies matter and how science plays a role in policy development.

NTDs comprise a category of over 20 diseases, ranging from parasitic infections to bacterial afflictions to snakebites. Many are treatable and preventable, especially with adequate funding and global support, and significant progress has been made towards control and eradication in the last 10 years. Much of this work has been championed by the World Health Organization (WHO), which leads and enacts global health policy, initiatives, and partnerships around the world. Accomplishing the WHO’s 2030 goals of vastly reducing the number of people affected by NTDs, achieving elimination of NTDs in 100 countries, and fully eradicating two NTDs [5], however, requires more work in a variety of sectors. This is complicated by the fact that a given country’s capacity to integrate WHO guidelines for disease control is directly linked to its national policies and ability to implement them.

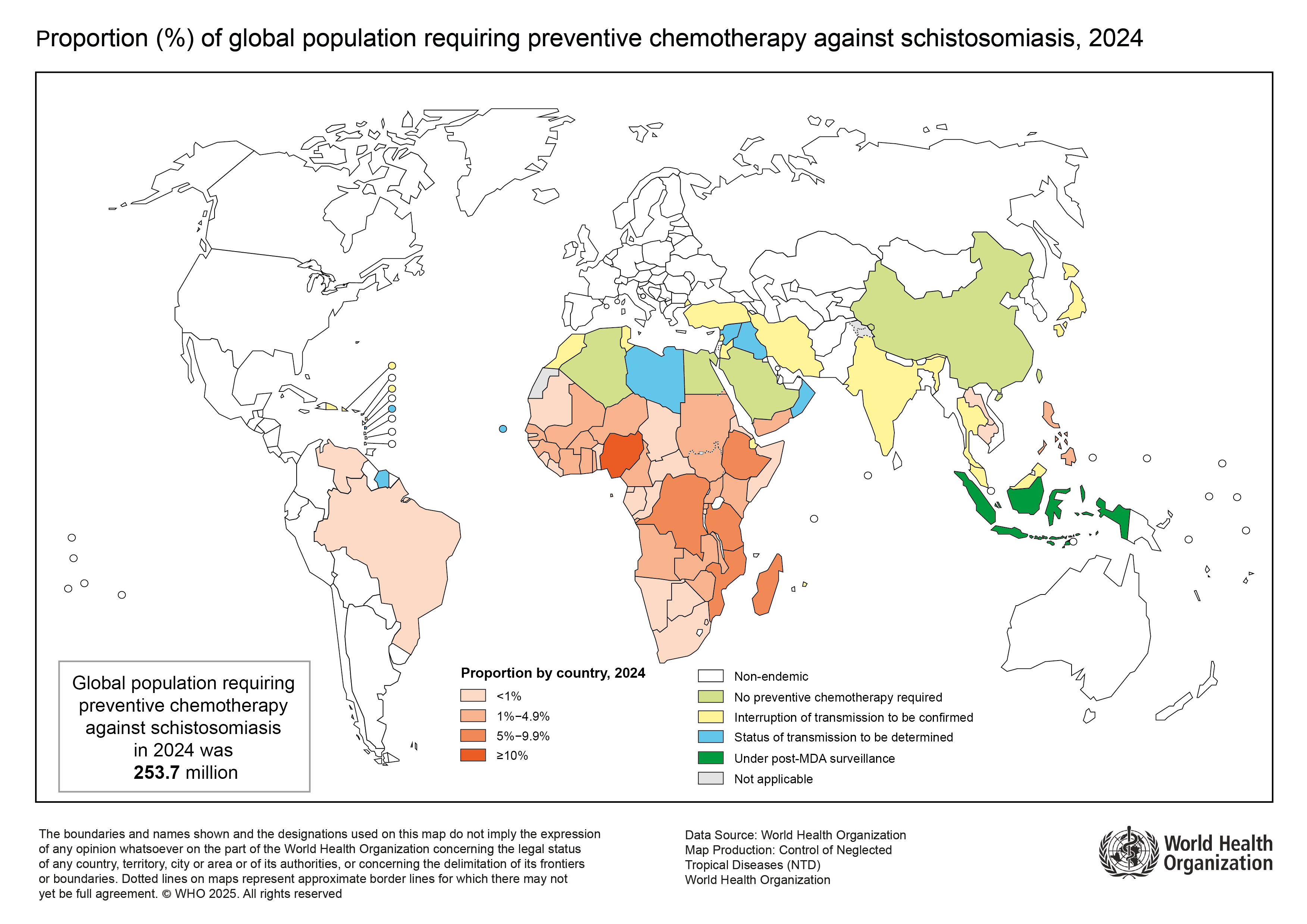

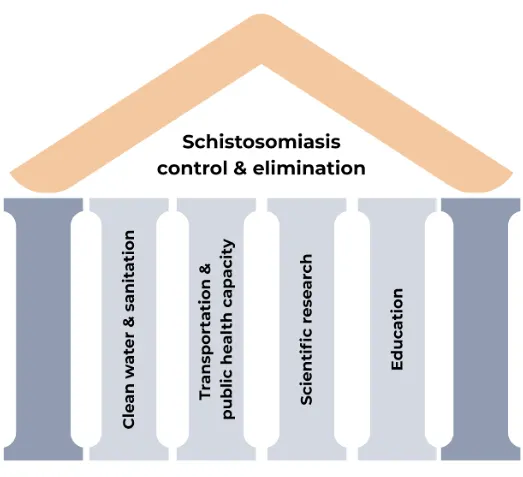

To illustrate the intersectionality of policies that impact NTDs, we will focus on schistosomiasis (pronounced: shi-stow-so-my-a-sis). This disease is caused by parasitic flatworms (Schistosoma spp.) that infect human intestines and urinary tracts [6]. Part of the worm’s lifecycle is spent in freshwater snails, which allows it to multiply and contaminate water sources (Figure 1). Schistosoma worms are spread to people by contact with contaminated freshwater, and the disease impacts over 250 million people globally. While the majority of infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa, schistosomiasis is an international disease, endemic to over 70 countries (Figure 2) [6]. Control and elimination of NTDs like schistosomiasis rely on work in and collaboration across a variety of sectors. For example, country-level policies addressing clean water and sanitation, transportation infrastructure, public health departments, scientific research, and investment in education can all contribute meaningfully to mitigating disease spread (Figure 3). Below, we discuss these policies in the context of schistosomiasis.

).](/images/blog_figures/2026_01_30_figure_1.webp)

Figure 1: A simple overview of the Schistosoma spp. transmission cycle involving humans, snails, freshwater bodies, and the various stages of the parasite that travels throughout those three environments (source: Laura Olivares Boldú / Wellcome Connecting Science; accessed through Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative).

).](/images/blog_figures/2026_01_30_figure_2.webp)

Figure 2: A map of the distribution of schistosomiasis in 2024, as represented by the proportion of a country’s population that requires praziquantel treatment (i.e., preventative chemotherapy). Praziquantel is referred to as "preventative chemotherapy" because it clears people of the worm infection, thereby preventing schistosomiasis disease. (Source: World Health Organization).

Figure 3: Policies targeting sectors across a variety of areas can contribute to NTD control and elimination. Here, we focused on clean water and sanitation, transportation infrastructure and public health departments, scientific research, and investment in education. However, addressing these areas alone will not result in the eradication of NTDs. The dark blue pillars represent other sectors that contribute towards disease control not discussed here, including but not limited to climate change adaptation, animal health, and public safety and national security. (This figure was made using Canva).

Clean water & sanitation are critical to disease control.

The worm that causes schistosomiasis is spread through the urine and feces of infected people into freshwater bodies (rivers, lakes, streams, etc.) [7]. Snails that live in these water sources become infected through human excreta, then spread human-infectious Schistosoma parasites back out into the water (Figure 1). When someone interacts with a contaminated water source, they can be infected, eventually becoming sick with schistosomiasis. Interactions with waterways like these can be a daily necessity in rural communities that lack accessible or affordable clean water.

Thus, policies that increase latrine coverage in rural communities or improve existing sanitation facilities and clean water access can reduce the spread of infectious material (worms) into the water and the frequency with which people contact these worms [8]. Importantly, these policies can also protect people from contracting other neglected and non-neglected diseases.²

Local infrastructure policies determine public health capacity.

A drug called praziquantel is used to treat schistosomiasis. According to guidelines set by the WHO, this essential medication should be delivered to communities with a high prevalence of schistosomiasis annually. Global policies like these, informed by scientific research and deliberated by national officials and other experts, are key to NTD control and aim to support all endemic countries.³

However, WHO recommendations lack both the locality-specific details and funding needed to implement these policies in endemic communities. Thus, national-level policies regulating developmental infrastructure and public health departments shape the capacity for success. For example, access to diagnostics and treatment for schistosomiasis may be impacted by a lack of public health department staff to serve communities in need and suitable roadways to reach remote areas [9,10]. If these limitations prevent communities from receiving treatment at the recommended frequency or with the recommended coverage, disease transmission will continue. If a human vaccine for schistosomiasis is ever deployed, these limitations may pose significant challenges to its distribution.⁴

Scientific research drives progress for interventions.

Science policy generally exists in two forms: science for policy and policy for science. In the context of NTDs, science for policy primarily refers to the scientific research that informs WHO and country-level policies, as discussed above, while policy for science is focused on the structural and systematic support of scientific research.

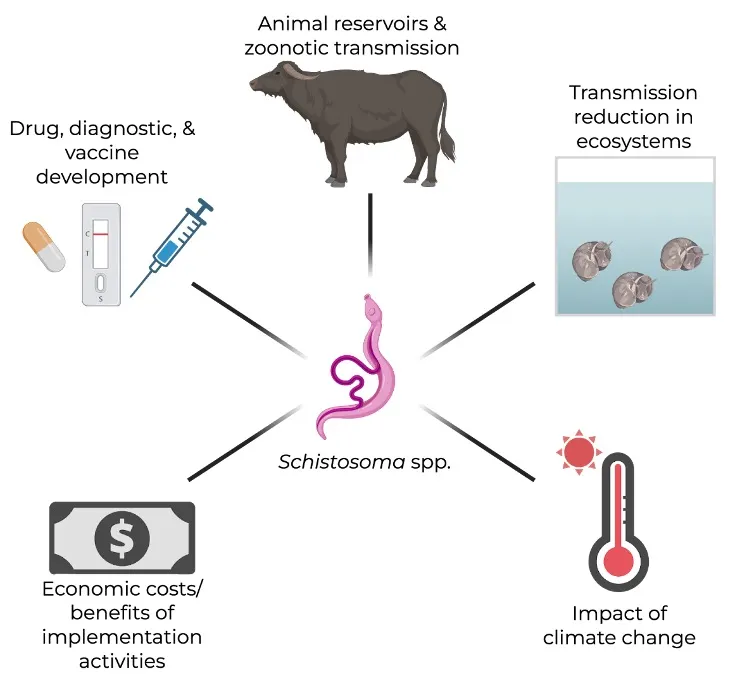

Despite the importance of the diverse scientific research being performed on NTDs, research funding has been decreasing since the early 2000s, falling well below the funding levels of many other diseases [11,12]. Critical ongoing schistosomiasis research includes: vaccine development [13], the role of animals and potential zoonotic transmission [14], reducing the snail population in freshwater ecosystems [15], understanding how transmission may be impacted by climate change [16,17], and assessing the economic costs and benefits of control interventions or vaccine deployment (Figure 4) [18,19]. Research in these areas improves the capacity to control disease with new tools and awareness, is conducted by interdisciplinary and multinational scientists, and is made possible through governmental and non-governmental funding. Indeed, global collaboration and policies for science that enable these research endeavours are necessary for future progress towards the elimination of schistosomiasis and other devastating NTDs.

Figure 4: A sampling of schistosomiasis research areas that may impact policy development towards the control and elimination of schistosomiasis from local communities. (This figure was made using Biorender).

Education improves outcomes of interventions.

Foundational to the success of current and future efforts to control schistosomiasis is the understanding of its transmission. Local educational policies informing impacted communities about disease symptoms/diagnosis and mechanisms to reduce transmission are critical. National educational policies could be adopted to supplement control programs, and several manuals to guide education programs in endemic countries have been developed [20,21].

Trust, built from knowledge, is a critical component of the successful implementation of disease control interventions, whether that be praziquantel administration or constructing sanitation facilities. When communities are equipped with knowledge to manage their health, compliance with treatments increases, and behavioral shifts can have cascading effects for disease reduction [22,23]. Unsurprisingly, the WHO cites the need for education and collaboration with local departments of education in their guidelines to control schistosomiasis.³ᵃ

Global funding is foundational for continued progress against NTDs.

While the WHO has done critically important work to develop scientifically rigorous policies and guidelines, recent actions deprioritizing and eliminating some major global health investments have made these tasks more difficult. Just last week, the U.S. completed its withdrawal from the WHO [24], making coordination between the WHO and U.S. officials and technical experts more difficult. This currently leaves the WHO in a financial bind, as it previously sourced 16–18% of its revenue from the U.S. [25]. Any reduction in funding will directly impact the WHO’s ability to act as a global facilitator for the control and elimination of NTDs like schistosomiasis [26]. As a direct result of the U.S.’s decision to withdraw funding, the WHO indicated that at least 47 mass NTD treatment campaigns have been delayed, and these funding cuts are expected to postpone targeted achievements and biomedical research progress [27].

Furthermore, the U.S. also dissolved the U.S. Agency for International Development last year, which was responsible for managing and distributing funds towards global health efforts, including NTDs [28]. This reduced funding for NTD control efforts, combined with the U.S. government’s decision to deprioritize research and development funding for many NTDs and international projects [29], is a concerning trend that undercuts progress towards reducing the global disease burden and promoting a healthier future for us all.

The U.S. first appropriated funding for NTDs in 2006 [30]. 20 years later, one-sixth of the global population is still affected by NTDs. Continued funding and research support are still needed.

Refer to our Further Reading, Resources, and Footnotes sections below to learn more about schistosomiasis and other NTD research, funding, and elimination efforts.

Recognition:

This article was authored by SNAP members Emily Selland and Becca Blyn. Emily is a Planetary Health scientist currently researching the socio-ecological determinants of Schistosoma spp. transmission and capacity for intervention. Becca is an infectious disease and immunology researcher studying the immune response to malaria and ways to improve malaria vaccine efficacy.

Special thanks to our fellow SNAP members who provided feedback on this blog: Kassandra Fernandez, an engineering education researcher with a background in medical microbiology, Jordan Williams, a pharmacologist with a background in drug development for rare and neglected diseases, and Emma Scales, a fungal biologist and former technical writer.

Further Reading:

A multi-chapter report could arguably be written on the way science policy has and continues to influence the transmission and control of neglected tropical diseases. Below, we recommend several additional resources, specific to schistosomiasis, for further reading in no particular order.

- Writing from Joy Nthiwa, schistosomaisis epidemiologist at the University of Nairobi, on Medium

- Morbidity from chronic schistosomiasis infections:

- Female Genital Schistosomiasis: A Silent Threat to Women’s Health and Gender Equality. (2024, October 14). Expanded Special Project for Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases. https://espen.afro.who.int/female-genital-schistosomiasis-silent-threat-womens-health-and-gender-equality

- Delphine Pedeboy, Female genital schistosomiasis: my personal account and key recommendations to the global health community, International Health, Volume 15, Issue Supplement_3, December 2023, Pages iii12–iii13, https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihad097

- The Global Schistosomiasis Alliance’s blog

- Social contexts and considerations of schistosomiasis and broad NTD control and research:

- Bruun, B., & Aagaard-Hansen, J. (2008). The social context of schistosomiasis and its control: An introduction and annotated bibliography. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331212/9789241597180-eng.pdf

- Hirsch, L. A., & Martin, R. (2022). LSHTM and Colonialism: A report on the Colonial History of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (1899– c.1960). London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.04666958

- Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation

- Zoonotic Schistosoma threats:

- Janoušková, E., Clark, J., Kajero, O., Alonso, S., Lamberton, P. H. L., Betson, M., & Prada, J. M. (2022). Public Health Policy Pillars for the Sustainable Elimination of Zoonotic Schistosomiasis. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases, 3. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/tropical-diseases/articles/10.3389/fitd.2022.826501/full.

- China’s historical campaigns to control schistosomiasis:

- Lv, S., Zhou, L.-G., Xu, J., Li, S.-Z., Bergquist, R., Utzinger, J., & Zhou, X.-N. (2025). From endemic shadows to the light of dawn: The 120-year journey of China’s anti-schistosomiasis chariot. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 14(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-025-01395-5

- Knowledge gaps for scientific research on Schistosoma spp. and transmission:

- Mwinzi, P. N., Chimbari, M., Sylla, K., Odiere, M. R., Midzi, N., Ruberanziza, E., Mupoyi, S., Mazigo, H. D., Coulibaly, J. T., Ekpo, U. F., Sacko, M., Njenga, S. M., Tchuem-Tchuente, L.-A., Gouvras, A. N., Rollinson, D., Garba, A., & Juma, E. A. (2025). Priority knowledge gaps for schistosomiasis research and development in the World Health Organization Africa Region. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 14(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-025-01285-w

- Historical perspectives on policies for the control of schistosomiasis:

- Sandbach, F. R. (1976). The history of schistosomiasis research and policy for its control. Medical History, 20(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025727300022663

Footnotes:

- See more on Disability Adjusted Life Years from NTDs:

- Hotez, P. J., Alvarado, M., Basáñez, M.-G., Bolliger, I., Bourne, R., Boussinesq, M., Brooker, S. J., Brown, A. S., Buckle, G., Budke, C. M., Carabin, H., Coffeng, L. E., Fèvre, E. M., Fürst, T., Halasa, Y. A., Jasrasaria, R., Johns, N. E., Keiser, J., King, C. H., … Naghavi, M. (2014). The Global Burden of Disease Study 2010: Interpretation and Implications for the Neglected Tropical Diseases. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(7), e2865. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002865

- For a comprehensive overview of country-level water-related policies from the perspective of a different pathogen, see:

- Weets, C. M., & Katz, R. (2024). Global approaches to tackling antimicrobial resistance: A comprehensive analysis of water, sanitation and hygiene policies. BMJ Global Health, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013855

- See comprehensive WHO guidelines for Schistosomiasis and 2 other Neglected Tropical Diseases:

- WHO launches new guideline for the control and elimination of human schistosomiasis. (2022, February 22). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/22-02-2022-who-launches-new-guideline-for-the-control-and-elimination-of-human-schistosomiasis

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2016). Guidelines for the management of snakebites, 2nd ed. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290225300

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2018). Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy. New Delhi: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290226383

- Read about a vaccine cold-chain to understand how it complicates the logistics of vaccine delivery:

- What is a cold chain? (n.d.). UNICEF. Retrieved January 28, 2026, from https://www.unicef.org/supply/what-cold-chain

References:

- Brief summary - World NTD Day 2025. (n.d.). World Health Organization. Retrieved January 28, 2026, from https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-ntd-day/2025/brief-outline

- Masterson, V., & Geldard, R. (2024, October 24). What are neglected tropical diseases — and what are we doing about them? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/10/what-is-neglected-tropical-diseases-day/

- https://worldntdday.org/

- Adams, P. (2025, June 5). “Neglected tropical diseases” now face even more neglect. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/goats-and-soda/2025/06/05/g-s1-70255/neglected-tropical-diseases-usaid-cuts-pharmaceuticals

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352

- Schistosomiasis - Status of schistosomiasis endemic countries: 2024. (n.d.). World Health Organization. Retrieved January 28, 2026, from https://apps.who.int/neglected_diseases/ntddata/sch/sch.html

- Schistosomiasis. (2024, June 7). CDC DPDx — Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Concern. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/schistosomiasis/index.html

- Reitzug, F., Ledien, J., & Chami, G. F. (2023). Associations of water contact frequency, duration, and activities with schistosome infection risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 17(6), e0011377. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011377

- Stothard JR, Sousa-Figueiredo JC, & Navaratnam AMD. (2013, July). Advocacy, policies and practicalities of preventive chemotherapy campaigns for African children with schistosomiasis. Expert Reivew of Anti-Infective Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.2013.811931

- Adeyemo, Sunday & Are-Daniel, Obehi & Adeleke, Folasade & Olabode, Eniola & Maleka, Abdulwaris & Odunlami, Akintade & Ajayi, Ayodele & Abdulsalam, Hussain & Nafiu, Rabiu & Usman, Yunusa. (2025). Barriers in the control of schistosomiasis with mass distribution of praziquantel in Bauchi State, Nigeria: a phenomenological study. Discover Health Systems. 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44250–025–00286–8.

- Pai, M. (2020, January 29). Record Funding For Global Health Research, But Neglected Tropical Diseases Remain Neglected. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/madhukarpai/2020/01/29/record-funding-for-global-health-research-but-neglected-tropical-diseases-remain-neglected/

- Dattani, S. (2024, June 25). Funding to study neglected tropical diseases and develop new technologies is very limited. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/data-insights/funding-to-study-neglected-tropical-diseases-and-develop-new-technologies-is-very-limited

- Kim, J., Davis, J., Lee, J., Cho, S.-N., Yang, K., Yang, J., Bae, S., Son, J., Kim, B., Whittington, D., Siddiqui, A. A., Carter, D., & Gray, S. A. (2024). An assessment of a GMP schistosomiasis vaccine (SchistoShield®). Frontiers in Tropical Diseases, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2024.1404943

- Salas-Coronas, J., Bargues, M. D., Fernández-Soto, P., Soriano-Pérez, M. J., Artigas, P., Vázquez-Villegas, J., Villarejo-Ordoñez, A., Sánchez-Sánchez, J. C., Cabeza-Barrera, M. I., Febrer-Sendra, B., De Elías-Escribano, A., Crego-Vicente, B., Fantozzi, M. C., Diego, J. G.-B., Castillo-Fernández, N., Borrego-Jiménez, J., Muro, A., & Luzón-García, M. P. (2024). Impact of species hybridization on the clinical management of schistosomiasis: A prospective study. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 61, 102744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2024.102744

- Selland, E. K., Jouanard, N., Guisse, A., Seck, M., Lund, A. J., López-Carr, D., Sack, A., Dossou Magblenou, L., De Leo, G., Doruska, M. J., Barrett, C. B., & Rohr, J. R. (2025). Rice-Fish Co-Culturing for Sustainability, Food Security, and Disease and Poverty Reduction. bioRxiv, 2025.11.14.688524. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.11.14.688524

- Hansen, J. (2024, August 5). Forecasting climate’s impact on a debilitating disease. Stanford Report. https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2024/08/forecasting-climate-s-impact-on-a-debilitating-disease

- Asare, K. K., Mohammed, M.-D. W., Aboagye, Y. O., Arndts, K., & Ritter, M. (2025). Impact of Climate Change on Schistosomiasis Transmission and Distribution — Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050812

- Lo, N. C., Bogoch, I. I., Blackburn, B. G., Raso, G., N’Goran, E. K., Coulibaly, J. T., Becker, S. L., Abrams, H. B., Utzinger, J., & Andrews, J. R. (2015). Comparison of community-wide, integrated mass drug administration strategies for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: A cost-effectiveness modelling study. The Lancet. Global Health, 3(10), e629–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00047-9

- Yamey, G., McDade, K. K., Anderson, R. M., Bartsch, S. M., Bottazzi, M. E., Diemert, D., Hotez, P. J., Lee, B. Y., McManus, D., Molehin, A. J., Roestenberg, M., Rollinson, D., Siddiqui, A. A., Tendler, M., Webster, J. P., You, H., Zellweger, R. M., & Marshall, C. (2025). Vaccine value profile for schistosomiasis. Vaccine, 64, 126020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.05.068

- Lucien, K. F. H., Nkwelang, G., & Ejezie, G. C. (2003). Health education strategy in the control of urinary schistosomiasis. Clinical Laboratory Science: Journal of the American Society for Medical Technology, 16(3), 137–141. https://clsjournal.ascls.org/content/ascls/16/3/137.full.pdf

- Pan American Health Organization. (1990). Health education in the control of schistosomiasis. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/44784

- Burnim, M., Ivy, J. A., & King, C. H. (2017). Systematic review of community-based, school-based, and combined delivery modes for reaching school-aged children in mass drug administration programs for schistosomiasis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 11(10), e0006043. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006043

- Torres-Vitolas, C. A., Trienekens, S. C. M., Zaadnoordijk, W., & Gouvras, A. N. (2023). Behaviour change interventions for the control and elimination of schistosomiasis: A systematic review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 17(5), e0011315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011315

- Foulkes, I., & Mitchell, O. (2026, January 23). US officially leaves World Health Organization. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn9zznx8qdno

- Kates, J., Michaud, J., Moss, K., Dawson, L., & Rouw, A. (2025, January 28). Overview of President Trump’s Executive Actions on Global Health. KFF. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/overview-of-president-trumps-executive-actions-on-global-health/

- Mazumdar, S. (2020, April 23). World Health Organization: What does it spend its money on? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/world-health-organization-what-does-it-spend-its-money-on-136544

- Neglected tropical diseases further neglected due to ODA cuts. (2025, June 4). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/04-06-2025-neglected-tropical-diseases-further-neglected-due-to-oda-cuts

- Enserink, M. (2025, May 20). Crippling tropical diseases threaten to surge after U.S. funding cuts. Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/crippling-tropical-diseases-threaten-surge-after-u-s-funding-cuts

- Impact Global Health. (2025, November 10). State of disunion: The impact of US funding cuts on global health R&D. Impact Global Health. https://www.impactglobalhealth.org//insights/report-library/state-of-disunion-the-impact-of-us-funding-cuts-on-global-health-rd

- The U.S. Government and Global Neglected Tropical Disease Efforts. (2024, October 29). KFF. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/the-u-s-government-and-global-neglected-tropical-diseases/